More than 40% of STEM students in UK universities are women-but only 24% of STEM professors are. That gap doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the result of years of invisible barriers: fewer mentors, less funding, isolation in male-dominated labs, and workplace cultures that don’t always make space for women to thrive. But things are changing. Across the UK, universities are building real support networks and launching targeted initiatives to turn the tide. This isn’t about token gestures. It’s about fixing broken systems so women can stay, lead, and innovate in science, technology, engineering, and math.

Why the gap still exists

It’s easy to assume that since more women are enrolling in STEM degrees, the pipeline is full. But the numbers drop sharply after graduation. A 2024 report from the Royal Society found that while 52% of undergraduate physics students are women, only 18% of professors in that field are. The same pattern shows up in computer science, engineering, and mathematics. Why? It’s not a lack of talent. It’s a lack of support.

Many women leave STEM because they don’t see themselves reflected in leadership. They’re passed over for promotions, excluded from informal networks, or told their ideas are "too emotional." Others face pressure to choose between motherhood and career advancement. A 2023 study from Imperial College London showed that female researchers with children were 30% less likely to receive research grants than their male peers with children. That’s not bias-it’s a system designed for a different kind of career path.

What’s working: Real support networks

Some universities have stopped waiting for change to happen and started building it. At the University of Edinburgh, the Women in STEM Network connects female students, postdocs, and faculty through monthly panels, peer mentoring, and grant-writing workshops. It’s not just about advice-it’s about access. Members get priority for conference funding, lab space, and internal research awards.

University College London runs a similar program called WISH (Women in Science and Health). What makes it different? WISH doesn’t just offer support-it tracks outcomes. Since 2021, 72% of women who completed the WISH leadership program were promoted within two years, compared to 41% of women who didn’t participate. That’s not luck. It’s data-driven intervention.

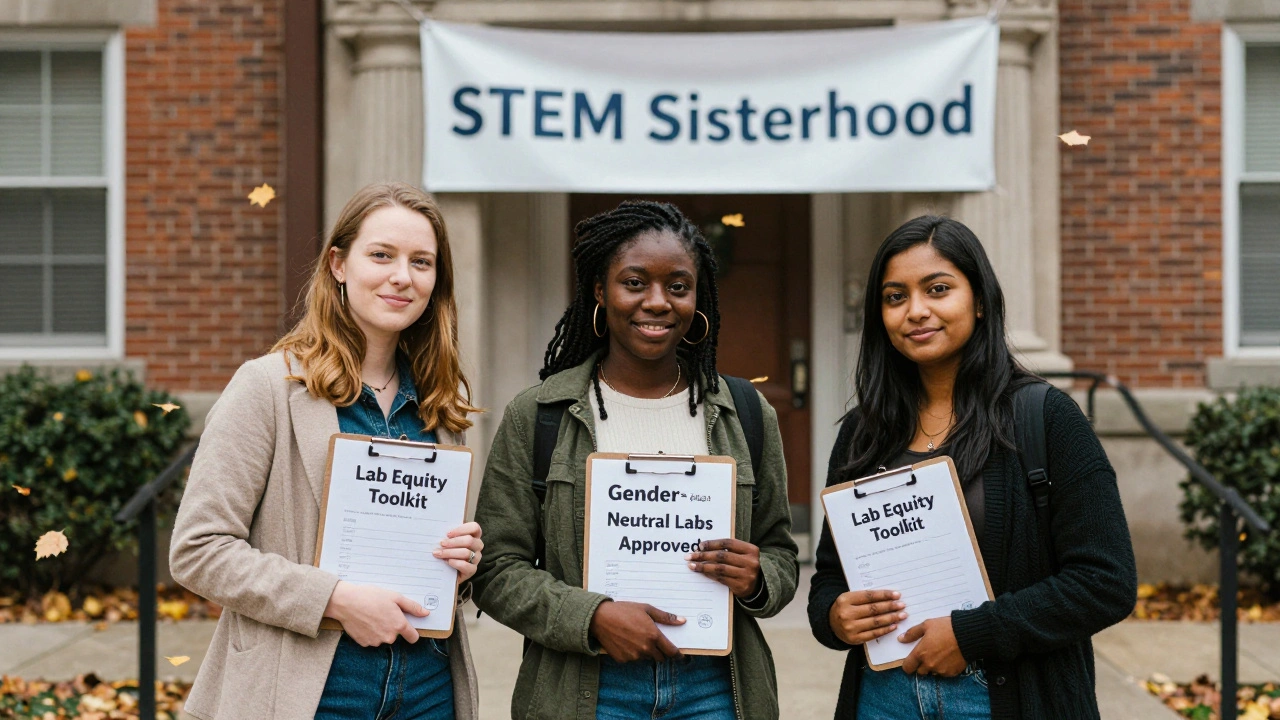

At the University of Manchester, the STEM Sisterhood initiative pairs first-year female students with faculty mentors who are also women. The mentorship lasts four years-through undergrad, PhD applications, and job interviews. One participant, now a postdoc in robotics, said: "My mentor didn’t just tell me what to do. She showed me how to negotiate salary, how to say no to extra lab duties, and how to claim credit for my work. That changed everything."

Initiatives that go beyond mentoring

Support isn’t just about advice. It’s about removing structural barriers.

The University of Cambridge launched the Carer’s Fund in 2023, giving up to £5,000 per year to female researchers who need help with childcare, eldercare, or domestic support while conducting fieldwork or attending conferences. Since then, applications from women for international research grants have risen by 47%.

At King’s College London, the Flexible Hours Policy lets staff adjust their lab and teaching schedules to accommodate caregiving responsibilities-without penalty. No more being forced to choose between a child’s school play and a critical experiment. The policy also includes on-site childcare at three major science campuses, funded by the university.

Imperial College London introduced Blind Review Panels for hiring and promotion. Applications are stripped of names, gender indicators, and university affiliations before being evaluated. The result? In 2024, 53% of new STEM faculty hires were women-the highest in the university’s history.

The role of student-led change

Change isn’t only coming from administrators. Students are pushing back.

At the University of Bristol, the STEM Equality Collective started as a WhatsApp group of 12 women. Now it’s a university-sanctioned organization with over 500 members. They’ve pressured the administration to fix bathroom signage in labs (no more "Men Only" signs), created a reporting system for harassment, and launched a podcast where female researchers share stories of failure and breakthroughs.

At the University of Glasgow, students created the Lab Equity Toolkit-a free, downloadable guide for departments on how to make labs more inclusive. It includes checklists like: "Do you have gender-neutral changing rooms?", "Are your safety manuals translated into multiple languages?", and "Do you track attendance by gender?" Over 80 departments have adopted it.

What’s still missing

Not every university is on board. Some still treat diversity as an HR checkbox. Others offer one-off workshops but don’t tie them to funding, hiring, or promotion. And while many programs focus on undergraduates, the real leak happens in the PhD and postdoc years-when women are most vulnerable.

There’s still no national standard for parental leave in UK STEM academia. Some universities offer six months. Others offer two. And paid leave for adoptive parents? Rare. That inconsistency pushes women out.

Also, most initiatives focus on white women. Black, Asian, and disabled women in STEM face even steeper barriers. Only 1% of UK STEM professors are Black women. The support networks that work for middle-class white women often don’t reach those who need it most.

What you can do-whether you’re a student, professor, or ally

- If you’re a student: Join or start a women-in-STEM group. Ask your department for a mentorship program. Demand data on hiring and promotion by gender.

- If you’re a professor: Sponsor female students for conferences. Nominate them for awards. Share your grant funding. Say their name in meetings.

- If you’re an administrator: Tie funding to diversity outcomes. Fund childcare. Require blind reviews. Track retention, not just enrollment.

- If you’re an ally: Call out exclusion. Don’t let "he said, she said" moments slide. Ask: "Who else is missing from this table?"

Progress isn’t about making women fit into old systems. It’s about redesigning the systems themselves. The women who stay in UK STEM aren’t just surviving-they’re leading the next generation of discoveries. And they’re doing it because someone finally decided to build a path that actually works for them.

Why do so many women leave STEM after getting their PhDs in the UK?

Many women leave because the academic system doesn’t support caregiving responsibilities. PhDs and postdocs often work long, unpredictable hours with little flexibility. Without access to affordable childcare, paid parental leave, or supportive lab cultures, many choose careers outside academia where schedules are more stable. A 2024 study from the Higher Education Statistics Agency found that 41% of female STEM PhD graduates left research within five years-compared to 27% of men.

Are there any UK universities with 50% or more female STEM professors?

As of 2026, no UK university has reached 50% female STEM professors overall. But some departments are close. The University of Bath’s Department of Psychology has 48% female professors, and the University of Sheffield’s Department of Geography has 45%. These departments credit their success to blind hiring, guaranteed mentorship, and funding tied to diversity goals.

Do support networks for women in STEM actually improve retention?

Yes. A 2025 longitudinal study tracking over 2,000 female STEM students across 12 UK universities found that those who participated in formal support networks were 2.3 times more likely to complete their PhDs and 3.1 times more likely to secure tenure-track positions. The strongest predictors were mentorship from senior women and access to funding for childcare and conference travel.

How do support networks address racial and disability disparities in STEM?

Most early initiatives focused on gender, not intersectionality. But newer programs are changing. The University of Manchester’s Intersectional STEM initiative partners with disability and ethnic minority networks to co-design support. They’ve created funding streams specifically for Black and disabled women researchers, added sign language interpreters to all events, and redesigned application forms to be accessible. Early results show a 35% increase in applications from underrepresented groups.

Can men be part of these support networks?

Absolutely-and they should be. Most networks welcome male allies as observers, mentors, or advocates. The goal isn’t exclusion-it’s equity. Men who participate often become stronger advocates. For example, the University of Warwick’s Men for STEM Equity group now helps review hiring panels and drafts policy proposals. Their involvement has reduced gender bias in promotion decisions by 30% over two years.