Not all subjects work the same way. You can’t memorize calculus like you memorize Shakespeare, and you can’t drill vocabulary like you drill physics formulas. Yet most students use the same study method for everything-rereading notes, highlighting everything, cramming the night before. That’s why so many people feel like they’re working hard but getting nowhere. The truth? Revision needs to change based on what you’re studying.

STEM Subjects: Build Understanding, Not Memory

STEM-science, technology, engineering, and math-isn’t about recalling facts. It’s about solving problems you’ve never seen before. If you walk into an exam and see a question that looks nothing like your practice problems, you’re not failing because you didn’t study. You’re failing because you studied the wrong way.

Here’s what actually works for STEM:

- Do problems. Not just the ones in the textbook. Find extra ones online, from past exams, from study groups. The more variations you’ve seen, the better you’ll recognize patterns.

- Explain your steps out loud. If you can’t walk someone through how you solved a differential equation, you don’t really understand it. Record yourself solving a problem and listen back. Where did you hesitate? That’s your weak spot.

- Use active recall, not passive review. Close your book and try to redraw the Krebs cycle from memory. Then check. Repeat. This builds neural pathways, not just temporary familiarity.

- Study in chunks. Don’t spend three hours on one topic. Do 45 minutes of thermodynamics, then switch to organic chemistry. Your brain needs to reset.

One student I worked with kept failing her physics exams. She had perfect notes. She’d reread them every night. But when she tried to solve a problem, she froze. We switched her to doing five new problems every day, timed, with no notes. Within two weeks, her grade jumped from a D to a B+. She wasn’t memorizing-she was learning how to think.

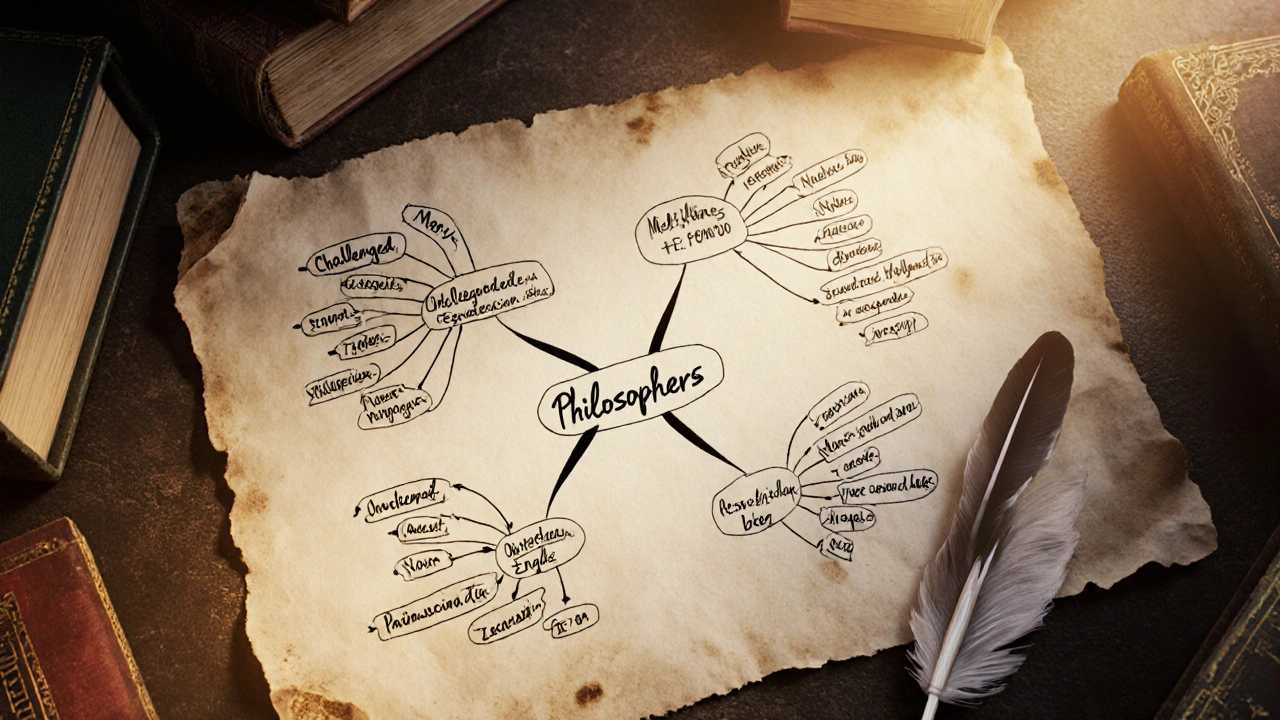

Humanities: Connect Ideas, Don’t Just Memorize Dates

History, philosophy, literature-they’re not about dates, names, or quotes. They’re about arguments. Who said what? Why? What were they reacting to? How does it connect to today?

Most students write out essay plans like this:

- Marx on capitalism

- Engels on class struggle

- Quote from The Communist Manifesto

That’s not revision. That’s a to-do list. Real revision means building relationships between ideas.

Try this instead:

- Make argument maps. Draw a circle for each major thinker. Connect them with arrows labeled “challenged,” “expanded,” or “responded to.” See how ideas evolve.

- Turn every topic into a debate. “Was the French Revolution inevitable?” Write down three arguments for yes, three for no. Then defend the side you disagree with. This forces depth.

- Teach it to someone who knows nothing. Explain the Enlightenment to a 12-year-old. If you can’t simplify it without losing meaning, you don’t understand it well enough.

- Use spaced repetition for key concepts, not facts. Don’t memorize “1789: French Revolution.” Memorize “The French Revolution was the first modern revolution because it was driven by Enlightenment ideas, not royal succession disputes.” That’s a unit of understanding.

A student studying 19th-century literature kept mixing up Dickens and Hardy. We stopped her from listing novels. Instead, we made a chart: “What does each author say about poverty?” Dickens = systemic failure, Hardy = fatalism. That single comparison fixed her essay structure forever.

Languages: Speak Early, Even If You Sound Stupid

If you’re learning Spanish, Mandarin, or Arabic, your biggest enemy isn’t grammar. It’s fear. Fear of sounding wrong. Fear of being judged. That’s why so many people study for years and still can’t hold a conversation.

Language isn’t a subject you study. It’s a skill you practice-like playing guitar or swimming. You don’t become fluent by reading about swimming. You jump in.

Here’s how to revise for languages the right way:

- Speak from day one. Even if you only know five words. Say them out loud. Record yourself. Listen. Repeat. Don’t wait until you’re “ready.” There’s no such thing.

- Use shadowing. Play a short audio clip in your target language. Pause. Repeat it out loud, matching the rhythm and tone. Do this for 10 minutes a day. It rewires your mouth and ears.

- Label your world. Stick notes on your fridge, mirror, laptop: “puerta,” “agua,” “computer.” Your brain starts associating objects with words, not translations.

- Watch shows with subtitles-in the target language. Not English subtitles. Spanish subtitles for a Spanish show. Your brain learns context, not word-for-word translation.

- Build a “mini-conversation” bank. Memorize 5 real-life phrases: “How much is this?”, “I don’t understand, can you repeat?”, “What’s your favorite food here?” Use them every day. Real usage beats textbook grammar.

One learner spent six months memorizing verb conjugations and still couldn’t order coffee. Then she started chatting with language exchange partners for 15 minutes a day, using only the phrases she’d written down. Three months later, she was traveling alone in Colombia. She didn’t know all the rules. But she knew how to get by-and that’s what fluency starts with.

Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All

There’s a reason why flashcards work for vocabulary but fail for calculus. Each subject demands a different kind of thinking.

STEM = Problem-solving. You need to build mental models you can manipulate.

Humanities = Critical analysis. You need to see connections and argue from evidence.

Languages = Muscle memory. You need to train your brain to respond automatically.

Trying to use the same method for all three is like using a hammer to fix a leaky faucet. It might work for a minute, but it’s not the right tool.

Here’s a quick cheat sheet:

| Subject Type | What to Avoid | What to Do Instead |

|---|---|---|

| STEM | Rereading notes, highlighting, passive review | Solving new problems, explaining steps aloud, active recall with timed drills |

| Humanities | Memoizing quotes, listing dates, writing summaries | Argument mapping, debating ideas, teaching concepts simply |

| Languages | Grammar drills without speaking, translating word-for-word | Shadowing, labeling your environment, speaking daily, using real phrases |

What to Do When You’re Stuck

Even with the right method, you’ll hit walls. Here’s how to break through:

- If you’re in STEM and can’t solve a problem, step away for 20 minutes. Go for a walk. Come back and try again. Your brain solves problems in the background.

- If you’re in Humanities and your essay feels flat, ask: “So what?” Why does this idea matter? Who does it affect? Push past description into significance.

- If you’re learning a language and feel stuck, switch your input. Watch a YouTube video instead of reading a textbook. Listen to a podcast. Change the channel-your brain needs new input.

Don’t blame yourself. Blame the method. You’re not lazy. You’re just using the wrong tools.

Final Tip: Match Your Revision to Your Goal

Are you studying for a multiple-choice test? Then focus on recall. Flashcards, quizzes, timed drills.

Are you preparing for an essay exam? Then focus on connections. Argument maps, practice outlines, timed writing.

Are you trying to speak fluently? Then focus on output. Talk to yourself, record, repeat, correct.

Your revision strategy should match the exam-or the real-world skill-you’re building. Not the one you’re used to.

Stop studying harder. Start studying smarter. Tailor your method to the subject. That’s the only way you’ll see real progress-and actually remember what you learn.

Can I use the same study method for all my subjects?

No. STEM requires problem-solving practice, humanities need critical analysis, and languages demand active speaking. Using the same method for all three leads to shallow learning. Match your technique to the subject’s demands.

Why do I forget what I studied after a few days?

You’re probably reviewing passively-rereading or highlighting. That creates an illusion of knowing. Real retention comes from active recall: testing yourself without notes. Use flashcards, practice problems, or explain concepts out loud.

How much time should I spend on each subject per day?

Focus on quality, not hours. Two focused 45-minute sessions on STEM with active problem-solving are better than three hours of passive reading. For languages, 15-20 minutes of speaking daily beats one long grammar session. For humanities, 30 minutes of argument mapping is more effective than hours of note-copying.

Is it better to study one subject all day or switch between them?

Switch. Your brain learns better when you alternate between different types of thinking. Studying math for two hours, then switching to history, then practicing Spanish, helps you retain more. This is called interleaving-and it’s backed by cognitive science.

What if I don’t have time to use all these methods?

Start with one. Pick the subject you struggle with most. For STEM, do one new problem daily without notes. For humanities, write one argument map per week. For languages, speak for five minutes a day. Small, consistent actions beat cramming. Progress builds slowly-but it lasts.