On results day in the UK, thousands of students open their envelopes or log into portals with hearts pounding. Some get exactly what they were told they’d get. Others get far more. And some-far too many-get far less. The gap between predicted grades and achieved grades isn’t just a number on a screen. It’s a doorway to a university, or a slammed shut door with a waiting list notice taped to it.

What Predicted Grades Really Mean

Predicted grades aren’t guesses. They’re formal estimates made by teachers and school counselors based on mock exams, class performance, coursework, and past student trends. In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, these predictions are submitted through UCAS by early January for students applying to university that same year. For Scottish students, it’s similar, though the system runs on Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) timelines.

Teachers don’t just pull numbers out of thin air. A student consistently scoring 85% in A-level Biology, leading class discussions, and submitting high-quality coursework will likely get a predicted A*. But if that same student misses three weeks of school due to illness, or has inconsistent performance, the prediction might drop to a B. It’s not about potential-it’s about evidence.

Here’s the catch: predicted grades are often inflated. Schools know that higher predictions increase the chance of students getting offers from top universities. So, many institutions pad predictions by half a grade or more. A student who’s on track for a B might get an A predicted. A student averaging a C might get a B. It’s not dishonest-it’s strategic. But when results day comes and grades fall short, the system cracks under the pressure.

What Happens When Achieved Grades Fall Short

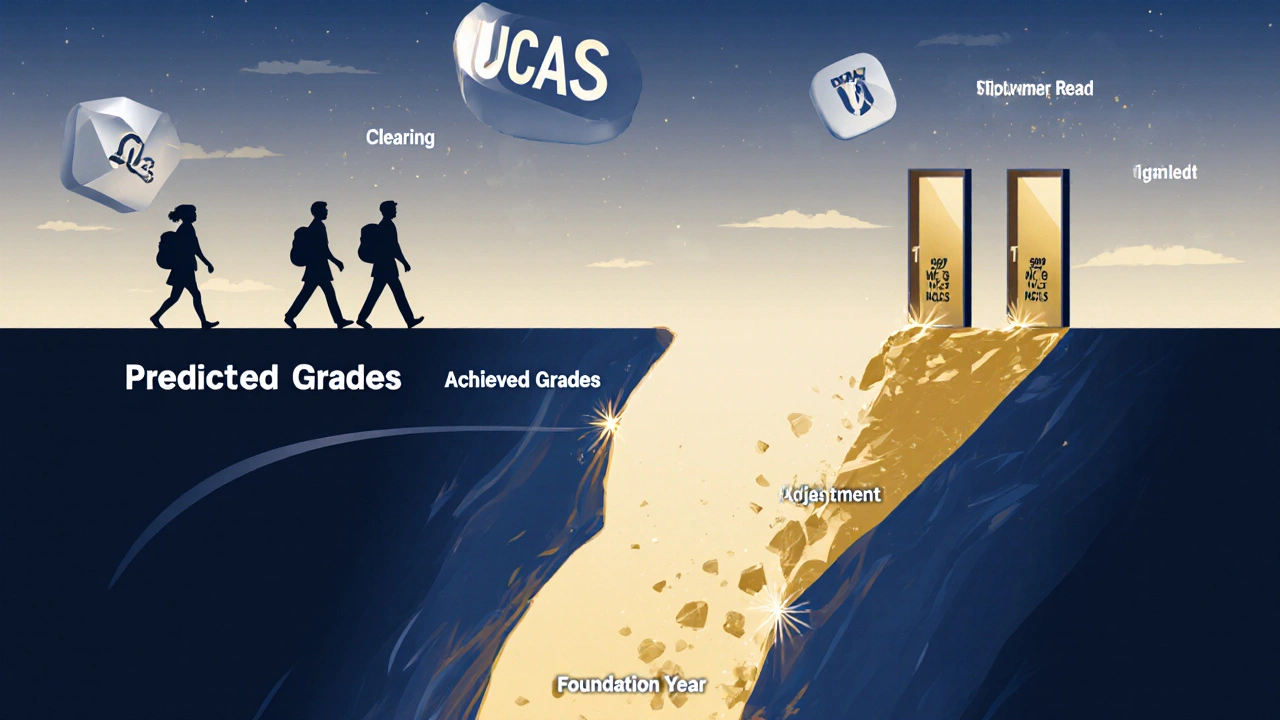

Results day in the UK is a high-stakes event. Universities receive grades in real time through UCAS. If your achieved grades are below your predicted grades, you might find yourself in “clearing”-the chaotic, fast-moving process where unplaced students scramble for remaining spots.

Some universities have strict policies. If you were offered a place based on predicted AAB and you got BBC, that offer is automatically withdrawn. No exceptions. No appeals. The system treats predicted grades as a contract.

But not all universities play by those rules. Many, especially mid-tier and newer institutions, are more flexible. They look at the full picture: personal statements, references, extracurriculars, and even how the student performed in interviews. One university in the Midlands told me they admitted 17% of students in 2024 who fell short of their predicted grades because their coursework portfolio showed exceptional depth in research.

Some universities even have “contextual offers.” These are lower grade requirements for students from under-resourced schools, low-income backgrounds, or areas with low university attendance. If you’re from a postcode where only 12% of students go to university, and you got a B when predicted an A, you might still get in. The university knows your grades don’t tell the whole story.

What Happens When Achieved Grades Are Higher

Getting better than predicted? That’s the dream. But it’s not always smooth sailing.

If you were predicted BBB and you got AAA, you might think you’re golden. You can use UCAS’s “Adjustment” service to try and move up to a more selective university. But here’s the reality: Adjustment is a race. Top universities like Oxford, Cambridge, and Imperial College London have very few spots open after the initial round. They don’t advertise them. They don’t wait. They fill them within hours.

One student in Manchester got A*A*A* in 2024 after being predicted ABB. She called six universities within an hour of results being released. Only one-University of Edinburgh-had a spot left in her chosen course. She took it. Another student, with similar grades, waited a day to think it over. By then, every place was gone.

Some universities won’t even consider Adjustment applicants unless they meet the original offer’s upper limit. For example, if your offer was AAB and you got AAA, you might still be rejected if the university only accepts Adjustment applicants who exceed the offer by two full grades. That’s not logic-it’s policy.

How Universities Actually Decide on Results Day

Behind the scenes, universities don’t just look at grades. They use algorithms, but not the kind you think.

Admissions teams have access to your full UCAS application: your personal statement, your reference, your school’s historical performance, even how many students from your school got into their university last year. If your school has a track record of overpredicting grades, your application gets flagged. If your school has a history of underperforming students who exceed predictions, they might give you the benefit of the doubt.

Some universities have “grade tolerance bands.” For example, a course might require ABB. If you got BBC, but your personal statement was outstanding and your reference praised your resilience, you might still get in. That’s not a rule-it’s a human decision made by an admissions officer who’s read 300 applications that morning and saw something real in yours.

But here’s the problem: not every university has that flexibility. Elite institutions are under pressure to maintain entry standards. They’re also under scrutiny from government bodies and league tables. If they admit too many students who didn’t meet their offer, their rankings drop. So they play it safe. They stick to the numbers.

The Real Impact on Students

For students, the gap between predicted and achieved grades isn’t just about university. It’s about identity. It’s about worth. It’s about whether you’re “good enough.”

One student in Bristol told me she cried for three hours after getting a C in Chemistry when she was predicted an A. She’d spent two years thinking she was on track for medicine. When her offer was withdrawn, she felt like a failure-even though her overall grades were still good enough for a biology degree.

Another student in Leeds got a B in Maths when predicted an A. He didn’t get into his dream engineering course. He took a gap year, retook the exam, and got an A. He’s now in his second year at Imperial. He says the setback taught him more than any lecture ever did.

There’s no universal answer. Some students thrive after being rejected. Others spiral. Mental health services at UK universities see a 40% spike in appointments on results day and the week after.

What You Can Do on Results Day

If your grades are lower than predicted:

- Don’t panic. Clearing opens at 8 a.m. BST. Have a list of backup courses ready.

- Call universities directly. Don’t just wait for UCAS to update. Admissions officers answer phones. Sometimes, they can make exceptions if you sound calm and prepared.

- Check if your school offers a “results day support line.” Many do.

- Consider a foundation year. It’s not a backup-it’s a path. Many students who take foundation years end up doing better than those who entered directly.

If your grades are higher than predicted:

- Act fast. Adjustment closes within days. Don’t delay.

- Have your UCAS ID, personal statement, and a list of target universities ready.

- Be realistic. Top courses fill fast. Don’t chase prestige if your current offer is solid.

If you’re unsure:

- Call your school’s careers advisor. They’ve seen this before.

- Use the UCAS Helpline (0371 468 0 468). They’re open 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. on results day.

- Remember: your grade doesn’t define your future. It just changes your starting point.

Why This System Still Exists

The UK’s predicted grade system was designed to allow universities to make early offers. It worked fine when only a third of students applied to university. Now, over half do. The system is outdated. It’s overburdened. It’s unfair.

Some countries use portfolio-based admissions. Others use interviews. A few have moved to test-optional models. The UK hasn’t. Why? Because changing it means rewriting decades of policy, training thousands of teachers, and rebuilding a national system.

But the cracks are showing. More schools are now submitting “realistic predictions.” More universities are asking for transcripts instead of relying on predictions. The trend is shifting-slowly.

For now, students must navigate a system that doesn’t always reflect their true ability. But knowing how universities respond-what they look for, what they ignore, and when they bend the rules-gives you power. You’re not just waiting for a grade. You’re preparing for a conversation.

What happens if my achieved grades are below my predicted grades?

If your achieved grades are below your predicted grades, your original university offer may be withdrawn. You’ll enter UCAS Clearing, where you can apply to courses with remaining spots. Some universities still accept you if your overall profile is strong, especially if you’re from a disadvantaged background or your school has a history of overpredicting grades.

Can I still get into a top university if I underperformed on results day?

It’s rare, but possible. Top universities like Oxford and Cambridge rarely admit students below their offer, unless there’s a documented personal hardship or exceptional context. Mid-tier universities are more flexible. If your personal statement, reference, or portfolio stood out, calling the admissions office directly can make a difference.

What is UCAS Adjustment and how does it work?

UCAS Adjustment lets students who exceeded their offer conditions apply to a more competitive course or university. You have five days after results day to use it. You must have met and exceeded your original offer by at least one grade. Spots are limited and fill quickly-often within hours. You need to contact universities directly to check availability.

Are predicted grades accurate?

Studies show that predicted grades in the UK are often too high. In 2023, over 58% of A-level students received higher predicted grades than their final results. This inflation happens because schools want to maximize university offers for their students. As a result, the system is increasingly seen as unreliable by universities.

Should I retake exams if I didn’t meet my predicted grades?

It depends. If your target course requires a specific grade (like medicine or engineering), retaking can be worth it. Many students who retake exams improve by a full grade. But consider the time and stress. A foundation year or alternative pathway might be less stressful and still lead to the same degree. Talk to your school’s careers advisor before deciding.