Writing a strong essay in the UK isn’t about sounding smart. It’s about showing you understand the topic well enough to back up your ideas with real proof. Professors don’t just want your opinion-they want to see that you’ve read the material, thought about it, and can connect it to your argument. That’s where evidence and quotes come in. But using them badly can hurt your grade more than not using them at all.

Why Evidence Matters More Than Opinions

Every essay you write should answer a question. Not just any question-something that requires analysis, not just summary. If you say, "Shakespeare’s Hamlet is tragic," that’s just a statement. But if you say, "Hamlet’s tragedy stems from his inability to act, as shown when he delays avenging his father despite having clear opportunity," now you’re making a claim. And claims need proof.

In UK universities, especially at undergraduate level, markers use a clear rubric: 30% of your grade often comes from how well you use sources. That means if you write 2,000 words and only drop in three vague quotes, you’re leaving points on the table. Evidence isn’t decoration. It’s the foundation. Every paragraph should link back to a source-whether it’s a book, journal article, historical document, or interview.

Choosing the Right Evidence

Not every quote or statistic is useful. A good piece of evidence does three things:

- It directly supports your point

- It’s from a credible source

- It adds something new-not just repeats what you already said

For example, if you’re writing about climate policy in the UK, quoting the 2023 Committee on Climate Change report that says "the UK is not on track to meet its 2030 emissions target" is stronger than quoting a newspaper editorial calling the government "incompetent." The report is official data. The editorial is opinion.

Look for peer-reviewed journals, government publications, and academic books. Avoid blogs, Wikipedia, or social media unless your tutor specifically allows it. Even then, treat them as starting points, not proof.

How to Integrate Quotes Smoothly

Quoting is not just copying and pasting. A poorly placed quote looks like you ran out of ideas. Here’s how to do it right:

- Introduce the quote-say who said it and why it matters. Example: "As historian Linda Colley argues in British Identities, national identity in the 18th century was shaped more by war than by culture."

- Insert the quote-use quotation marks and keep it short. Don’t quote whole paragraphs. One or two sentences max.

- Explain the quote-don’t assume the reader gets it. Say how it connects to your argument. Example: "This challenges the idea that British identity was built solely on shared language or religion, showing instead that external conflict played a central role."

Think of it like this: you’re not dropping a quote into your essay-you’re handing it to your reader with a note attached saying, "Here’s why this matters."

Paraphrasing: The Hidden Skill

Not every source needs to be quoted. In fact, most shouldn’t be. Paraphrasing-putting someone else’s idea into your own words-is often more valuable. It shows you understand the material, not just how to copy-paste.

Good paraphrasing means:

- Changing the sentence structure completely

- Using your own vocabulary

- Still citing the original source

Bad paraphrasing? Just swapping out a few words. For example:

Original: "The Industrial Revolution transformed rural economies into urban industrial centers."

Bad paraphrase: "The Industrial Revolution changed rural economies into urban industrial centres."

Good paraphrase: "Before factories took over, most British people lived and worked on farms. By the mid-1800s, over half the population had moved to cities to find jobs in manufacturing."

The second version doesn’t just reword-it expands, clarifies, and shows deeper understanding. That’s what markers look for.

When to Quote vs. When to Paraphrase

Here’s a simple rule:

- Quote when the exact wording matters-like a powerful phrase, a legal definition, or a unique perspective.

- Paraphrase when you’re summarizing ideas, explaining theories, or connecting concepts.

For example, quote this line from Virginia Woolf: "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction." It’s iconic. Changing it would lose its power.

But you can paraphrase this: "According to Foucault, power operates through institutions like schools and prisons, not just through force." You don’t need his exact words-you need to show you understand the idea.

Citing Sources Correctly

UK universities mostly use Harvard referencing. That means in-text citations with author and year, followed by a full reference list at the end.

Example in-text: (Smith, 2020)

Example in reference list:

Smith, J. (2020) Writing for Academia. London: Penguin Academic.

Don’t forget page numbers when quoting directly: (Jones, 2019, p. 47). Missing them is a common mistake-and it looks lazy.

Tools like Zotero or Mendeley can help manage references, but don’t rely on them blindly. Always double-check formatting. A single missing comma can cost you marks.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even good students trip up here. Watch out for:

- Over-quoting-if more than 20% of your essay is quoted, you’re not writing, you’re compiling.

- Drop quotes-inserting a quote without introducing or explaining it. This confuses the reader and looks like you’re hiding behind someone else’s words.

- Using outdated sources-in history or literature, older texts are fine. In science, law, or economics, use sources from the last 5-10 years.

- Forgetting to cite-even if you paraphrase. Plagiarism isn’t just copying. It’s failing to give credit.

One student I worked with rewrote a paragraph from a journal article, changed three words, and didn’t cite it. She thought she’d "made it her own." She failed the essay. The marker used Turnitin. It flagged every sentence.

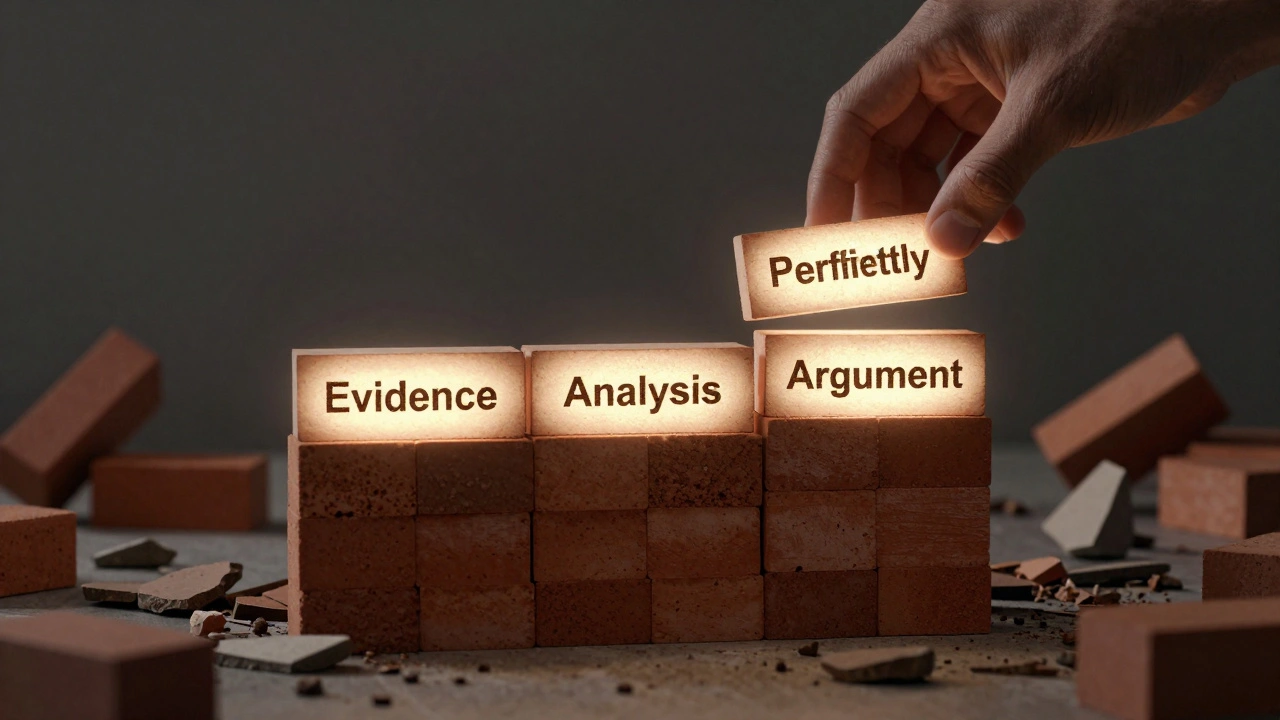

Building Your Argument, Not Just Listing Sources

The biggest mistake? Treating sources as a checklist. "I need five quotes, so I’ll find five." That’s not analysis. That’s stuffing.

Your argument should drive the sources-not the other way around. Start with your claim. Then ask: "What evidence supports this?" Then find it. Not the other way around.

Imagine you’re writing about gender roles in Victorian novels. Your claim: "Female characters in Dickens often serve as moral anchors, not just passive victims." Now find quotes that prove that. Don’t just grab every quote about women. Pick the ones that show strength, influence, or quiet resistance.

That’s how you turn a list of quotes into a real argument.

Final Tip: Read Like a Writer

When you read academic texts, don’t just absorb the content. Notice how the author uses evidence. How do they introduce a quote? Where do they paraphrase? How do they link sources to their own ideas?

Read one essay from your course that got a first-class mark. Highlight every piece of evidence. Then ask: "Why did they pick this? How does it move the argument forward?" You’ll start seeing patterns. And those patterns become your own writing habits.

Can I use quotes from novels in a history essay?

Yes, but only if you’re analyzing the novel as a historical source. For example, if you’re studying how Victorian society viewed class, you can use Dickens’ portrayal of poverty to reflect contemporary attitudes. But you must explain why the novel is relevant-not just drop a quote and assume it speaks for itself.

How many sources should I use in a 2,000-word essay?

There’s no magic number, but aim for 8-12 high-quality sources. That’s about one source every 150-250 words. More isn’t better if they’re weak or irrelevant. Focus on depth, not quantity.

What if I can’t find a source that supports my point?

Then your point might be too weak-or wrong. Good arguments are built on evidence, not wishes. If you’re struggling to find sources, revisit your thesis. Maybe you need to narrow it. Or maybe you need to adjust your stance to match what the literature shows.

Do I need to cite common knowledge?

No. Common knowledge includes widely accepted facts like "World War II ended in 1945" or "Shakespeare wrote Hamlet." But if you’re using a specific interpretation-like "Hamlet’s delay reflects Renaissance anxiety about action"-that’s not common knowledge. Cite it.

Can I use quotes from YouTube videos or podcasts?

Only if your tutor allows it, and only if the speaker is an expert in the field. A university professor giving a lecture on YouTube? Fine. A vlogger summarizing a book? Not reliable. Always check your department’s guidelines. When in doubt, stick to published academic work.